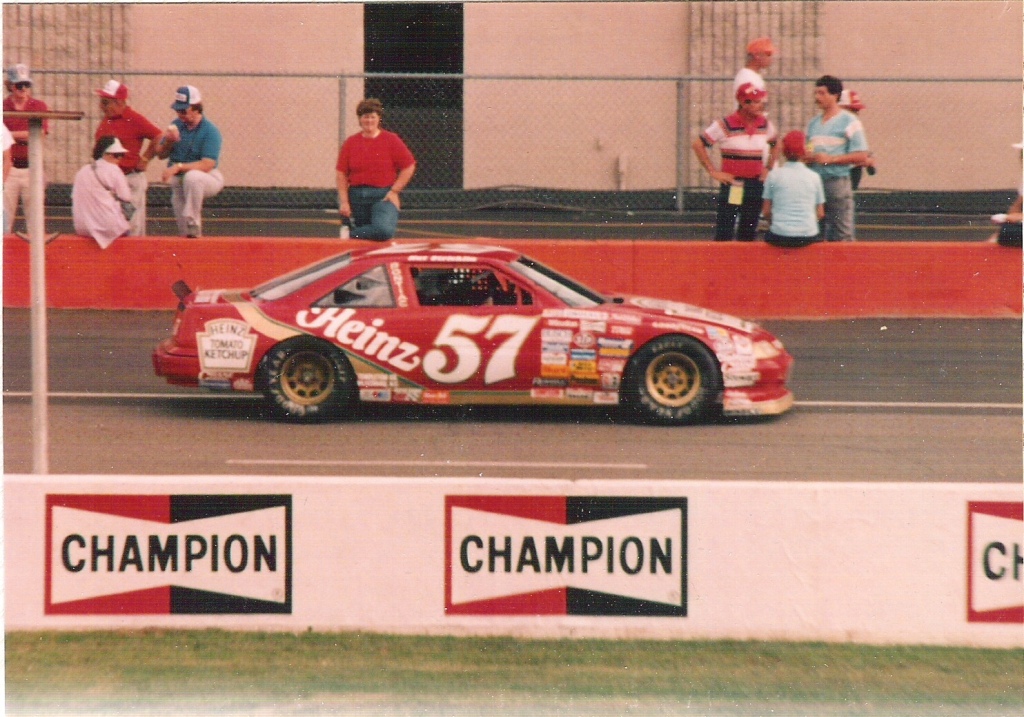

We talk a lot about NASCAR in the context of the “good ol’ days” around here. There’s no denying it, the last two decades of the 20th century were some of the best all-around experiences the sport of American stock car auto racing could ever hope to achieve. It’s a struggle to see our way around the rose tinted fog of nostalgia, but the hard facts show us a strong argument for this notion. The sweet spot of economic strength, accessible viewing opportunities, comparatively affordable sponsorship, and a talent pool that may have been the most refined and prepared of all time gave us all a truckload of memories and a strong desire to somehow “go back.” One of the first driver names that come to my mind when thinking of this Golden Age is Alabama’s Hut Stricklin. While the Dale Earnhardts and Jeff Gordons of the era will go down deservedly as the great ones, drivers like Stricklin help prove this theory of exceptionalism to my mind. While the 1987 NASCAR Dash series champion never quite reached the promised land of NASCAR superstardom at the Cup level, his competitiveness and ability to overachieve seemingly out of nowhere helped frame the strength of the combined field of competitors during this time.

“I was very fortunate to be racing when I did, and I’d like to see it get back to those days, but a lot has changed. I don’t think I’d fit in with this era of driver.” Hut Stricklin raced in an era where drivers had more responsibility for their machines, and much of the safety was quite literally governed via the driver’s seat. “Where I grew up racing against guys like the Allisons, Red Farmer, and Dave Mader as a young guy…you go down in the corner and put so much as a tire mark on their car, they will WRECK your ass! They would be the ones that have to get out of the car and scrub that tire mark off, so we learned to race clean.”

While all parties involved can agree today’s NASCAR racing can be wildly exciting with last lap wrecks and spectacularly risky moves, the near guaranteed safety was not a luxury held in the 20th century. “Today they can push and shove, beat and bang, and still feel fine when they get out of the car. I wasn’t taught to race that way. Look back at the ASA guys. Mark Martin, Rusty Wallace, Dick Trickle…those guys were the best on short tracks, but if they needed to back off a little and finish 2nd, they’d just beat you next week. They had to work on their own cars, fix their cars…these guys now when they wreck it’s, ‘Ope, oh well’ and they can drive or fly on home.”

Stricklin’s point about ASA shows another clear difference between the two eras. For better or worse, when money is available, the paths to the highest levels of NASCAR are fairly wide open. The need to scrap and develop in the local or regional racing series is much less of a prerequisite for the financially backed. “When I was racing, drivers had to start local. As you move up the ranks, guys would build a fan base, and when they get to Cup they’ve got that following. Guys today come up out of nowhere a lot of times, and there’s not much of a fan base coming with it.” This point is something that seems lost with a lot of fans asking the questions about current fan engagement. There’s not necessarily a “talent” issue, as good (and not so good) drivers come and go every single year. However, when Hut Stricklin was racing in NASCAR, nearly every single driver had a dedicated following before they even had their first official start. When Hut speaks, there’s a clear indication that he still loves racing, and follows it closely even as some detractors from his era claim to have left the sport for good. A lot of the conversation is naturally about “chasing history” and finding that golden age feeling again. In many ways, NASCAR is still chasing the feeling of a single race ran some thirty years ago.

In November 1992, what many believe to be the greatest NASCAR race of all time took place. The Hooters 500 at Atlanta represents a lot of what the sport has been trying to replicate in the Playoff era. Razor thin point standings, all-timer driver talent merged with promising newcomers, this race delivered everything desired organically and has had an effect on stock car racing ever since. Hut Stricklin was in that race, but unfortunately has the distinction of being the last place finisher. Driving for Larry Hedrick between fairly successful stints with Bobby Allison and Junior Johnson, Stricklin qualified the Kellogg’s number 41 in 19th and was looking to finish the season strong before moving to the new McDonald’s sponsored 27 car in 1993. One other facet of this race as an all-timer is how it started immediately with a crash among the leaders up front. As Brett Bodine and pole sitter Rick Mast spun into turn 1, both cars were sent sliding down the banking into traffic. Simultaneously, the field checked up and Stricklin bumped into the left rear of points leader (and childhood friend) Davey Allison, shooting the 41 down into the path of Bodine’s drifting number 26 car. The damage to Allison’s car and shake up of the field from the crash set course a series of events that we talk about to this day, and may never be able to duplicate without artificial intervention ever again. “[Hedrick] had just switched to Ford and we had a great race car…I was in a wrong spot at the wrong time. It was a pretty tremendous lick.” Stricklin collided with Brett Bodine at a pretty high rate of speed (I can still hear Benny Parsons shouting “oh nooo!” at the moment of impact on ESPN) causing both he and Bodine to require medical attention at a nearby hospital. “I had some sore ribs, but nothing broke. The worst thing, I had to test the next day with Junior Johnson back at the track. We made the test, got it done, but needless to say I was in some pretty good pain.”

None of us would trade away the aforementioned safety of today’s NASCAR, but driving hurt and in other cases providing relief is certainly a lost art form in stock car racing. Hut Stricklin should be remembered for many good reasons, but one of which should be his ability as a relief or even full blown substitute driver. “I did it a lot. I think a lot of people looked at me as easy to work with and very knowledgeable about the cars. It was so cool to drive with all of these teams, and work with all of these big sponsors…since they never had to worry about being embarrassed by my saying or doing something they didn’t like, it was always an honor. Anytime you went anywhere to relieve, you already knew 3/4ths of the guys on the team so I always felt comfortable.”

Going into the 1995 season, Hut Stricklin’s unique skills were called upon with a new venture. Long time Cup owner and drag racing legend Kenny Bernstein’s King Racing team (26 car) was taking a gamble with its rookie driver. Dirt Sprint Car racing’s own crowned royalty Steve Kinser certainly fit the bill for popularity and stature, but was extremely inexperienced in a NASCAR style vehicle. Stricklin was hired as a driving consultant for the team, and took to providing feedback for Kinser with a very elaborate pre-season training program. “They talked to me about going with them to test with Kinser, going to all sorts of tracks to get Kinser some experience. Nobody painted a picture that I was ever going to drive that car, it was all about trying to make Kinser as ready as we could.” Hut continues about the plan, “we’d take two cars, Steve and I, and I’d talk to him on the radio if he was pitching the car too much in a corner or going hard on the throttle. Those Cup cars were all about finesse then, and I could tell it was aggravating [Kinser]. It was a hard changeover for him.” As the ‘95 season started Kinser did indeed struggle and was involved in numerous incidents early on. After consecutive DNQs Kinser resigned from the team and Stricklin was named the driver for the rest of the season.

While some remember the King Racing organization as “on the way out” in 1995, Stricklin felt it was one of the best teams he was ever with. “The way it worked out, it was one of best I’d ever been with, we had everything it took to win races and it was a fun race team to be with. I loved driving for Kenny Bernstein.” The statistics back up this claim even further as pound for pound Hut Stricklin had one of his best seasons with multiple Top 10s and Top 5s and his first and only career pole late in the season at Rockingham. Still, even with the strong resources, Kenny Bernstein decided to close down the team late in the year, and much of the team’s performance was overshadowed by the Kinser resignation and subsequent shutdown. “It’s like the rug gets pulled out from under you” as Stricklin looks back at the instantaneous change of attitude a team closure announcement can bring, especially in the time long before the Cup charter system. While the precarious stability of Cup racing presents opportunities for strong characters like Stricklin, it has also produced even more unique job requirements to keep a car on the track.

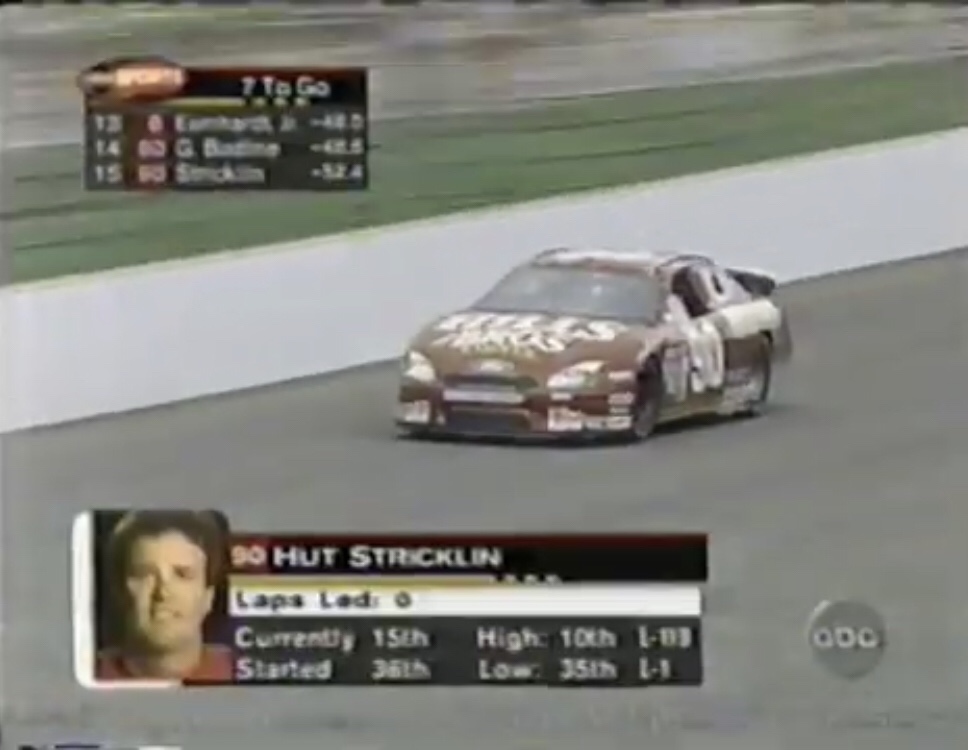

Hut Stricklin is one of many NASCAR drivers that had the privilege of racing for the late, great Junie Donlavey of Richmond, Virginia. While never the team with the biggest budget, Junie’s unique resourcefulness and eye for driving talent allowed the famous 90 car to still compete at a relatively high level next to the titans of Cup series. One issue in the late 90s however was the need for a crew chief, and the difficulty of getting one for the now struggling Virginia operation. “It was very hard to get an experienced crew chief to move up there to Richmond or come help us up there. Junie made a driver change for Indianapolis (2000), and I went up there to Richmond to drive and set the car up. We drove over to the track about 4 in the morning, got maybe an hour’s sleep before qualifying the car.” Hut, while pulling double duty to both set up and drive the car was able to make the Brickyard 400, and still had to effectively run the whole show during Sunday’s race. Deciding when to pit, the number of tires, and what adjustments to make to the car while also driving a 400 mile race at the world’s most famous speedway would possibly be too much to handle for most drivers, but the Hills Bros Coffee sponsored 90 kept getting faster. “I called all the shots from the car, told them what I wanted. We had good, fun guys, just not a lot of experience. The car was pretty good in race trim, and we went from the back to the front and got a pretty decent [14th place] finish, which was exceptional for what we had.”

While this Brickyard performance will forever be commendable, it exposed an issue with the team, primarily regarding the growing corporate sponsorship in NASCAR and the expectations that come with those business deals. Hills Bros Coffee was new to NASCAR and represented new corporate money that was taking an interest in the sport around the turn of the century. “One of the CEOs of the company and I became friends, and they wanted to know what it would take to have better performances, and I said we would need to move the team. We weren’t going to get the help we needed in Richmond.” Junie Donlavey, who at this time was entering his late 70s, stood firm and expressed no interest in moving the operation he made famous in his hometown. “Junie was dead set. I understood that and respected it, but for the sponsorship to get what they wanted they were just going to have to move to a different team.”

After Hills Bros moved to Bill Davis racing, Hut Stricklin soon joined both the sponsor and previous crew chief Philippe Lopez with whom helped some of Hut’s best performances, putting together what would end to be the final chapter of the Alabama driver’s long career. “We just couldn’t get going, it never was the right thing for us or me. I had heard Bill Davis was a great guy and all that…and maybe he is, but he hardly ever talked to me, he always seemed mad at the world. Maybe it was one of those things that wasn’t meant to be.” After a brake part failure in the Daytona 500 qualifying race kept the 23 car and Hut from qualifying for the Great American Race, Hut looks back, with good natured sarcasm, on the first racing impression that may have developed from that year’s Speedweeks. “You know it’s a really good way to get off on the right foot with an owner when your teammate [Ward Burton] wins the Daytona 500 and you can’t even make the show! (laughs) But sometimes it’s just one of those things.”

After Bill Davis made a change about 2/3rds of the way into the 2002 season, Hut Stricklin after 328 Cup races over 16 years, made the decision to retire from driving. “I had reached a point where I was ready for a change. I had bounced around and flim-flammed for a lot of teams and did some relief driving, and throughout that time I had been in numerous wrecks. I had cracked my sternum, broke my ribs a few times…I was beat up and I was ready to wash my hands of it. Still love racing, loved it when I walked away from it, but I was ready for something else.”

Hut Stricklin is still a fan, and always has been a fan of motorsports. While two decades removed from driving, Hut is very knowledgeable about the current state of affairs in NASCAR. “I always want to see our sport grow and get better. It’s not like it used to be, but for one I like that [the gen 7] still looks like a stock car.” Modern safety, charters, driver etiquette (or lack thereof), Stricklin weighs much of what was good then and what is good now in a way that a lot of fans as well as former drivers may lose in the shuffle. Still, there’s something to be said for old school hard work, and drivers from Stricklin’s era perfected fan engagement long before social media streamlined the process. Meeting the fans in the 20th century was a bit more personal, and required a lot of face time. Stricklin received one of the most valuable lessons in this concept very early in his career, from the best possible mentor. “I always looked at fans as the ones that paid us. When I came up in the sport I drove for Pontiac, and I got to do a lot of autograph sessions with Richard Petty. Some drivers leave when the ’time is up’ for these kind of appearances, but the King wouldn’t leave until the last fan got their autograph, and heck I’d stay right there with him. He taught me to cherish the fans, they put the food on your table. I never forgot that.”

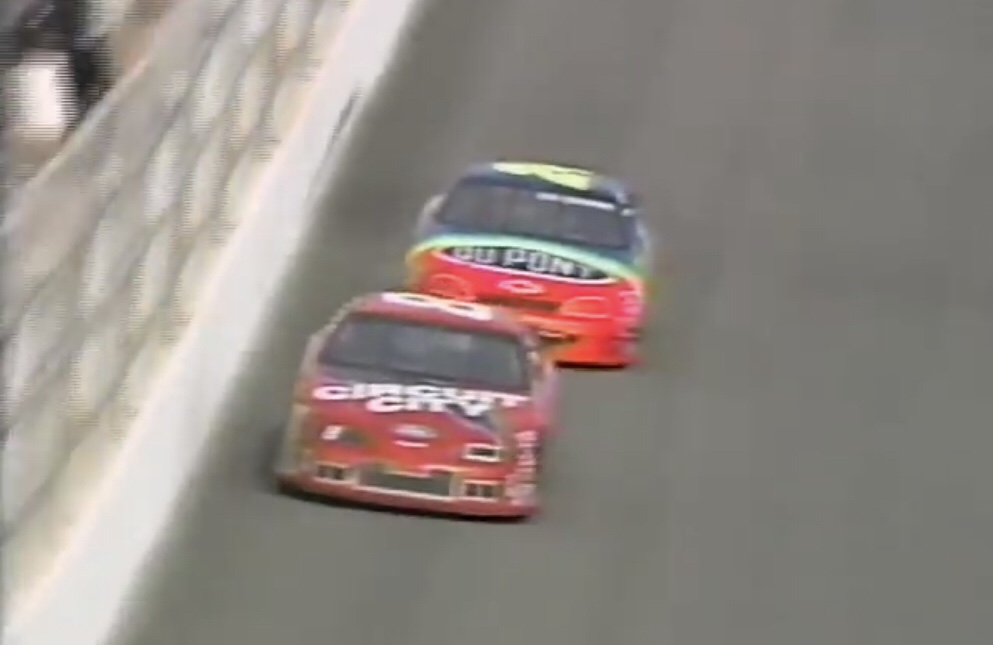

One last thing. I couldn’t have a conversation with Hut Stricklin without asking THE question. Could he have held off Jeff Gordon? “Yes,” Stricklin gives the easiest of answers when speaking about his best career Cup finish. In the 1996 Southern 500 Stricklin, driving for the Stavola Bros team had one of their best performances ever at Darlington. “We were so fast at the start, and maybe equal [to the leaders] shortly after.” During a time when Jeff Gordon was setting the standard for domination, a track and setup like that day’s Circuit City 8 car served as a bit of an equalizer. Stricklin was up front all day and was turning heads holding the lead after a late pit stop. “We short pitted towards the end. Ernie Irvin came out on fresh tires and hit us in the left fender like I weren’t even there, and the car got tight at the part of the run when we would normally be the fastest. When Jeff got to me, there wasn’t much I could do.”

Stricklin may have had to settle for 2nd that day, but the performance helped produce one of the great memories of one of NASCAR’s most historic events. Racing drivers are known for a 6th sense about their cars, and for a driver like Hut Stricklin on that Southern 500 weekend, he knew history was possible. “From the moment we unloaded that car on Friday, I was driving down pit road the first time, I keyed the radio and told Philippe ‘we got a good car.’” No matter the level of mechanical know-how, personal experience, or sensible dedication, when a driver straps on the helmet, the game becomes remarkably simple. When asked by his crew chief how he could tell this car would be so good before even taking a hot lap, the NASCAR stalwart responded in a way only a driver ever could…

“…I can feel it in the steering wheel.”

Follow Matt on Twitter for all things NASCAR!